Mark Knopfler - Wikipedia

51 languages- العربية

- Aragonés

- Asturianu

- تۆرکجه

- বাংলা

- Български

- Català

- Čeština

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- Ελληνικά

- Español

- Euskara

- فارسی

- Français

- Galego

- 한국어

- Հայերեն

- Hrvatski

- Ido

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Italiano

- עברית

- ქართული

- Lëtzebuergesch

- Lietuvių

- Magyar

- Македонски

- مصرى

- Nederlands

- 日本語

- Norsk bokmål

- Norsk nynorsk

- Occitan

- Polski

- Português

- Română

- Runa Simi

- Русский

- Simple English

- Slovenčina

- Slovenščina

- Ślůnski

- Српски / srpski

- Suomi

- Svenska

- ไทย

- Türkçe

- Українська

- Vèneto

- 中文

Edit links

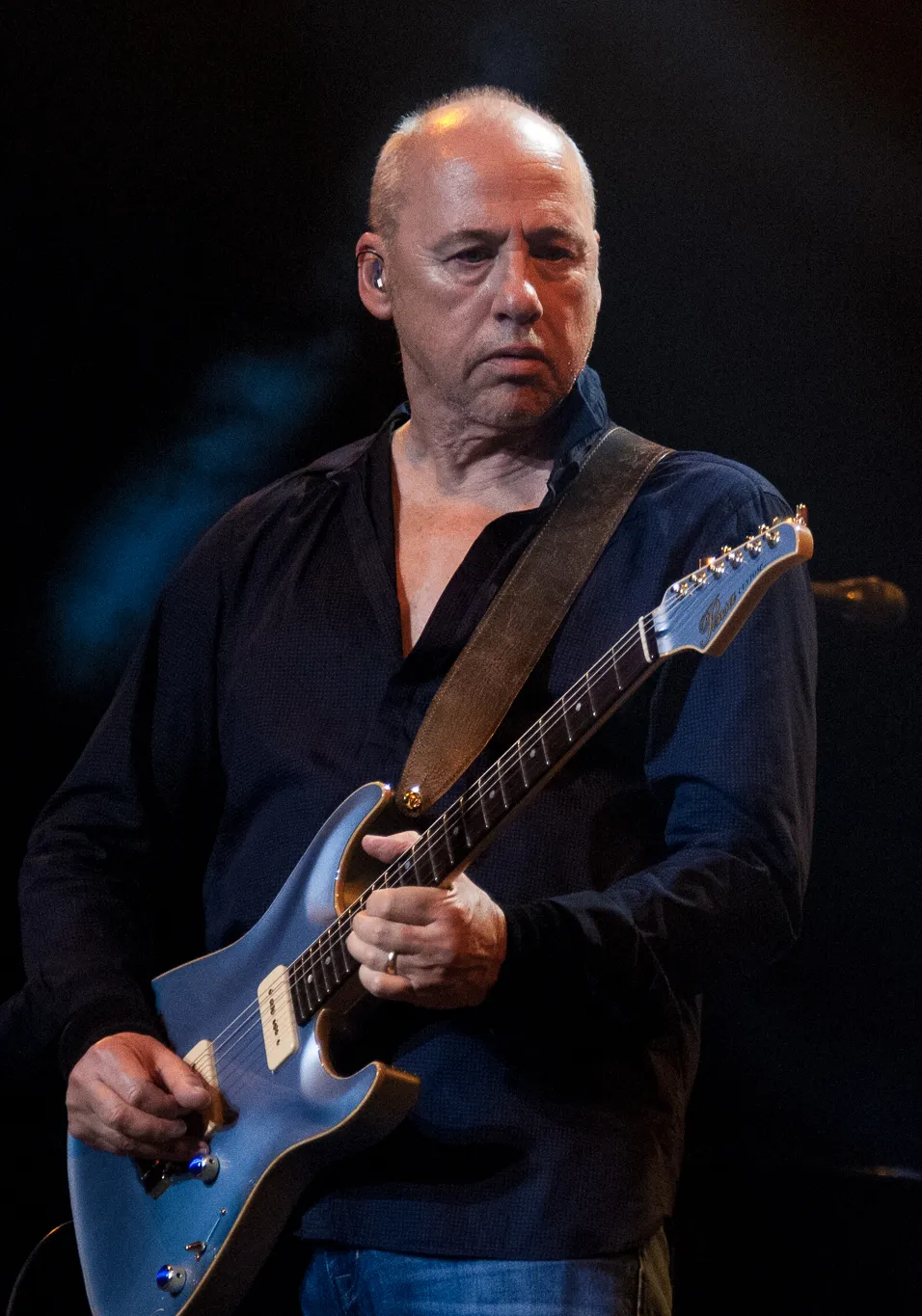

1949–1976: Early lifeedit

Mark Freuder Knopfler was born on 12 August 1949 in Glasgow, Scotland, to an English mother, Louisa Mary (née Laidler), and a Hungarian Jewish father, Erwin Knopfler.1011121314 His mother was a teacher and his father was an architect and a chess player who left his native Hungary in 1939 to flee the Nazis.15 Knopfler later described his father as a Marxist agnostic.16

The Knopflers originally lived in the Glasgow area where Mark’s younger brother David was born on 27 December 1952. Mark’s older sister Ruth was born in Newcastle, where Mark’s parents were married, in 1947.17 The family moved to Knopfler’s mother’s hometown of Blyth, near Newcastle, in North East England when he was seven years old. Mark had attended Bearsden Primary School in Scotland for two years; both brothers attended Gosforth Grammar School in Newcastle.

Originally inspired by his uncle Kingsley’s harmonica and boogie-woogie piano playing, Mark soon became familiar with many different styles of music. Although he hounded his father for an expensive Fiesta Red Fender Stratocaster electric guitar just like Hank Marvin’s, he eventually bought a twin-pick-upHöfner Super Solid for £50 (equivalent to £1,454 in 2023).18

In 1963, when he was 13, he took a Saturday job at the Newcastle Evening Chronicle newspaper earning six shillings and sixpence. Here he met the ageing poet Basil Bunting, who was a copy editor.19 The two had little to say to each other but, in 2015, Knopfler wrote a track in tribute to him.citation needed

At this time, Knopfler got around the country largely by hitchhiking, and also hitched through Europe a number of times.20

During the 1960s, he formed and joined several bands and listened to singers like Elvis Presley and guitarists Chet Atkins, Scotty Moore, B. B. King, Django Reinhardt, Hank Marvin, and James Burton. At the age of 16, he made a local television appearance as part of a harmony duo, with his classmate Sue Hercombe.18

In 1968, after studying journalism for a year at Harlow College,1821 Knopfler was hired as a junior reporter in Leeds for the Yorkshire Evening Post.22 During this time, he made the acquaintance of local furniture restorer, country blues enthusiast and part-time performer Steve Phillips, one year his senior, from whose record collection and guitar style Knopfler acquired a good knowledge of early blues artists and their styles. The two formed a duo called “The Duolian String Pickers”, which performed in local folk and acoustic blues venues.23 Two years later, Knopfler decided to further his education, and later graduated with a degree in English at the University of Leeds.24

In April 1970, while living in Leeds, he recorded a demo disc of an original song he had written, “Summer’s Coming My Way”. The recording included Knopfler (guitar and vocals), Steve Phillips (second guitar), Dave Johnson (bass), and Paul Granger (percussion). Johnson, Granger, and vocalist Mick Dewhirst played with Knopfler in a band called Silverheels; Phillips was later to rejoin Knopfler in the short lived side exercise from Dire Straits, The Notting Hillbillies.

Upon graduation in 1973, Knopfler moved to London and joined a band based in High Wycombe called Brewers Droop. This group had issued studio-recorded material before Knopfler joined, and went into the studio while Knopfler was a member – but Brewer’s Droop material with Knopfler remained unissued until appearing on their 1989 archival album The Booze Brothers.25

One night, while spending time with friends, the only guitar available was an old acoustic with a badly warped neck that had been strung with extra-light strings to make it usable. Even so, he found it impossible to play unless he finger-picked it, leading to the development of his signature playing style. He said in a later interview, “That was where I found my ‘voice’ on guitar.” After a brief stint with Brewers Droop, Knopfler took a job as a lecturer at Loughton College in Essex – a position he held for three years. Throughout this time, he continued performing with local pub bands, including the Café Racers.citation needed

By the mid-1970s, Knopfler devoted much of his musical energies to his group, the Café Racers. His brother David moved to London, where he shared a flat with John Illsley, a guitarist who changed over to playing bass guitar. In April 1977, Mark moved out of his flat in Buckhurst Hill and moved in with David and John. The three began playing music together, and soon Mark invited John to join the Café Racers.26

1977–1995: Dire Straitsedit

Main article: Dire Straits Knopfler with Dire Straits, 1979 Dire Straits’ first demos were recorded in three sessions in 1977, with David Knopfler as rhythm guitarist, John Illsley as bass guitarist, and Pick Withers as drummer. On 27 July 1977, they recorded the demo tapes of five songs: “Wild West End”, “Sultans of Swing”, “Down to the Waterline”, “Sacred Loving” (a David Knopfler song), and “Water of Love”. They later recorded “Southbound Again”, “In the Gallery”, and “Six Blade Knife” for BBC Radio London—and, finally, on 9 November, made demo tapes of “Setting Me Up”, “Eastbound Train”, and “Real Girl”. Many of these songs reflect Knopfler’s experiences in Newcastle, Leeds, and London, and were featured on their first album, the eponymous Dire Straits, which was released in the following year: “Down to the Waterline” recalled images of life in Newcastle; “In The Gallery” is a tribute to a Leeds sculptor and artist named Harry Phillips (father of Steve Phillips); and “Lions”, “Wild West End”, and “Eastbound Train” were all drawn from Knopfler’s early days in the capital.citation needed

On its initial release in October 1978, the album Dire Straits received little fanfare in the UK, but when “Sultans of Swing” was released as a single, it became a chart hit in the Netherlands and album sales took off – first across Europe, and then in the United States and Canada, and finally the UK. The group’s second album, Communiqué, produced by Jerry Wexler and Barry Beckett, followed in June 1979.

Their third album, Making Movies, released in October 1980, moved towards more complex arrangements and production, which continued for the remainder of the group’s career. The album included many of Mark Knopfler’s most personal compositions, most notably “Romeo and Juliet” and “Tunnel of Love”, with its intro “The Carousel Waltz” by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, which also featured in the 1982 Richard Gere film An Officer and a Gentleman. There were frequent personnel changes within Dire Straits from 1980 onwards, with Mark Knopfler and John Illsley the only members to remain throughout the group’s 18-year existence. In 1980 whilst the recording sessions for Making Movies were taking place, tensions between the Knopfler brothers reached a point where David Knopfler decided to leave the band for a solo career.27 The remaining trio continued the album, with Roy Bittan from Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band guesting on keyboards and session guitarist Sid McGinnis on rhythm guitar, although he was uncredited on the album. After the recording sessions were completed, keyboardist Alan Clark and Californian guitarist Hal Lindes joined Dire Straits as full-time members for the On Location tour of Europe, North America, and Oceania.28

In September 1982, the group’s fourth studio album Love Over Gold was released. This featured the tracks “Private Investigations”, “Telegraph Road”, “Industrial Disease”, “It Never Rains”, and the title track of the album, “Love Over Gold”. Shortly after the album’s release, Pick Withers left the band.

In early 1983, with Love Over Gold still in the albums charts, the band released a four-song EP titled ExtendedancEPlay. Featuring the hit single “Twisting by the Pool”, this was the first output by the band that featured new drummer Terry Williams, (formerly of Rockpile and Man). An eight month long Love over Gold Tour followed which finished with two sold-out concerts at London’s Hammersmith Odeon on 22 and 23 July 1983. In March 1984 the double album Alchemy Live was released, which documented the recordings of these final two live shows. It was also released in VHS video and reached number three in the UK Albums Chart, and was reissued in DVD and Blu-ray format in 2010.

During 1983 and 1984, Mark Knopfler was also involved with other projects outside of Dire Straits, some of which other band members contributed towards. Knopfler and Terry Williams played on Phil Everly’s and Cliff Richard’s song “She Means Nothing To Me”, which reached the Top 10 in the UK Singles Chart in February 1983, taken from the album “Phil Everly”. Knopfler had also expressed his interest writing film music, and after producer David Puttnam responded2930 he wrote and produced the music score to the film Local Hero. The album was released in April 1983 and received a BAFTA award nomination for Best Score for a Film the following year.3132 Alan Clark also contributed, and other Dire Straits members Illsley, Lindes and Williams played on one track, “Freeway Flyer”, and Gerry Rafferty contributed lead vocals on “The Way It Always Starts”. The closing track on the album and on the credits in the film is the instrumental “Going Home: Theme of the Local Hero” which was released as a single and became a popular live staple for Dire Straits, entering the band’s repertoire from 1983 onwards.3334

“Local Hero” was followed in 1984 by Knopfler’s music scores for the films Cal (soundtrack) and Comfort and Joy, both of which also featured Terry Williams, as well as keyboardist Guy Fletcher.28 Also during this time Knopfler produced Bob Dylan’s Infidels album, as well as Knife by Aztec Camera. He also wrote the song “Private Dancer” for Tina Turner’s comeback album of the same name to which other Dire Straits members John Illsley, Alan Clark, Hal Lindes and Terry Williams contributed. Knopfler also contributed lead guitar to Bryan Ferry’s album Boys and Girls, released in June 1985.

Knopfler performing in Dublin, 1981 Dire Straits’ biggest studio album by far was their fifth, Brothers in Arms. Recording of the album started at the end of 1984 at George Martin’s Air Studios in Montserrat with Knopfler and Neil Dorfsman producing.35 There were further personnel changes. Guy Fletcher joined the band as a full-time member, so the group now had two keyboardists, while second guitarist Hal Lindes left the band early on during the recording sessions and was replaced in December 1984 by Jack Sonni, a New York-based guitarist and longstanding friend of Knopfler (although Sonni’s contribution to the album was minimal).36 The then permanent drummer Terry Williams was released from the recording sessions after the first month and temporarily replaced by jazz session drummer Omar Hakim, who re-recorded the album’s drum parts within three days before leaving for other commitments.3738 Williams would be back in the band as a full-time member for the music videos and the 1985–1986 Brothers in Arms world tour that followed.39

Released in May 1985, Brothers in Arms became an international blockbuster that has now sold more than 30 million copies worldwide, and is the fourth best selling album in UK chart history.4041Brothers in Arms spawned several chart singles including the US # 1 hit “Money for Nothing”, which was the first video played on MTV in Britain. It was also the first compact disc to sell a million copies and is largely credited for launching the CD format as it was also one of the first DDD CDs ever released,42 Other successful singles were “So Far Away”, “Walk of Life”, and the album’s title track. The band embarked on a 1985–1986 Brothers in Arms world tour of over 23018 shows which was immensely successful.

After the Brothers in Arms world tour Dire Straits ceased to work together for some time, Knopfler concentrating mainly on film soundtracks. Knopfler joined the charity ensemble Ferry Aid on “Let It Be” in the wake of the Zeebrugge ferry disaster. The song reached No. 1 on the UK Singles Chart in March 1987. Knopfler wrote the music score for the film The Princess Bride, released at the end of 1987.

Mark Knopfler also took part in a comedy skit (featured on the French and Saunders show) titled “The Easy Guitar Book Sketch” with comedian Rowland Rivron and fellow British musicians David Gilmour, Lemmy from Motörhead, Mark King from Level 42, and Gary Moore. Phil Taylor explained in an interview that Knopfler used Gilmour’s guitar rig and managed to sound like himself when performing in the skit.43

Dire Straits regrouped for 11 June 1988 Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute concert at Wembley Stadium, in which they were the headline act, and were accompanied by Elton John and Eric Clapton,44 who by this time had developed a strong friendship with Knopfler. Jack Sonni and Terry Williams both officially left the band shortly afterwards.45 In September 1988 Mark Knopfler announced the official dissolution of Dire Straits, saying that he “needed a rest”.46 In October 1988, a compilation album, Money for Nothing, was released and reached number one in the United Kingdom.47

In 1989, Knopfler formed the Notting Hillbillies,18 a band at the other end of the commercial spectrum. It leaned heavily towards American roots music – folk, Blues and country music. The band members included keyboardist Guy Fletcher, with Brendan Croker and Steve Phillips. For both the album and the tour Paul Franklin was added to the line-up on pedal steel. The Notting Hillbillies sole studio album, Missing…Presumed Having a Good Time was released in 1990, and Knopfler then toured with the Notting Hillbillies for the remainder of that year. He further emphasised his country music influences with his 1990s collaboration with Chet Atkins, Neck and Neck, which won three Grammy awards. The Hillbillies toured the UK in early 1990 with a limited number of shows. In this low-key tour the band packed out smaller venues such as Newcastle University.

Knopfler with Dire Straits performing in Belgrade, 10 May 1985 In 1990, Knopfler, John Illsley, and Alan Clark performed as Dire Straits at Knebworth, joined by Eric Clapton, Ray Cooper, and guitarist Phil Palmer (who was at that time part of Eric Clapton’s touring band), and in January the following year, Knopfler, John Illsley and manager Ed Bicknell decided to reform Dire Straits. Knopfler, Illsley, Alan Clark, and Guy Fletcher set about recording what turned out to be their final studio album accompanied by sidemen Phil Palmer, pedal steel guitarist Paul Franklin, percussionist Danny Cummings and Toto drummer Jeff Porcaro.

The follow-up to Brothers in Arms was finally released in September 1991. On Every Street was nowhere near as popular as its predecessor, and met with a mixed critical reaction, with some reviewers regarding the album as an underwhelming comeback after a six-year break. Nonetheless, the album sold well and reached No. 1 in the UK. Session drummer Chris Whitten joined Dire Straits as they embarked on a gruelling world tour featuring 300 shows in front of some 7.1 million ticket-buying fans. This was to be Dire Straits’ final world tour; it was not as well received as the previous Brothers in Arms tour, and by this time Mark Knopfler had had enough of such huge operations. Manager Ed Bicknell is quoted as saying “The last tour was utter misery. Whatever the zeitgeist was that we had been part of, it had passed.” John Illsley agreed, saying “Personal relationships were in trouble and it put a terrible strain on everybody, emotionally and physically. We were changed by it.“48 This drove the band into the ground, and ultimately led to the group’s final dissolution in 1995.

Following the tour, Knopfler took some time off from the music business. In 1993, he received an honorary music doctorate from the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. Two more Dire Straits albums were released, both live albums. On the Night, released in May 1993, documented Dire Straits’ final world tour. In 1995, following the release of Live at the BBC (a contractual release to Vertigo Records), Mark Knopfler quietly dissolved Dire Straits and launched his career as a solo artist. Knopfler later recalled that, “I put the thing to bed because I wanted to get back to some kind of reality. It’s self-protection, a survival thing. That kind of scale is dehumanizing.“49 Knopfler would spend two years recovering from the experience, which had taken a toll on his creative and personal life.

Since the break-up of Dire Straits, Knopfler has shown no interest in reforming the group. However, keyboardist Guy Fletcher has been associated with almost every piece of Knopfler’s solo material to date, while Danny Cummings has also contributed frequently, playing on three of Knopfler’s solo album releases All the Roadrunning (with Emmylou Harris), Kill to Get Crimson, and Get Lucky. In October 2008 Knopfler declined a suggestion by John Illsley that the band should reform. Illsley said that a reunion would be “entirely up to Mark”; however, he also observed that Knopfler was enjoying his success as a solo artist.50 When asked about a possible reunion, Knopfler responded, “Oh, I don’t know whether to start getting all that stuff back together again”, and that the global fame Dire Straits achieved in the 1980s “just got too big”.50

In 2018, the band were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Knopfler did not attend the induction ceremony, however remaining members John Illsley, Guy Fletcher and Alan Clark were in attendance to accept the award on behalf of the band.

In November 2021 John Illsley published his autobiography My Life in Dire Straits, in which he confirms that Knopfler has no interest in reforming Dire Straits, which he again reiterated in an interview in November 2023. He reflected that the band members had “reached the end of the road” after the end of their final world tour in 1992, and that he was “pretty happy” when the band’s run came to an end, recalling feeling “mentally, physically and emotionally exhausted” by the time Dire Straits disbanded.5152 At the time, Illsley also said “I can openly admit to you that I really enjoyed the success of the band, I’m speaking for Mark as well, we both really enjoyed it. It comes with a certain amount of stress, obviously. You’ve got to really dig deep sometimes to keep it working. I think Mark said – and I hope I’m quoting him correctly here – but he said that success is great, but fame is what comes out of the exhaust pipe of a car. It’s something you don’t really want”.53

Dire Straits remain one of the most popular British rock bands as well as one of the world’s most commercially successful bands, with worldwide album sales of more than 120 million.54

1996–present: Solo careeredit

Knopfler performing in Bilbao, 2001 Knopfler’s first solo album, Golden Heart, was released in March 1996. It featured the UK single “Darling Pretty”. The album’s recording sessions helped create Knopfler’s backing band, which is also known as The 96ers. It features Knopfler’s old bandmate Guy Fletcher on keyboards. This band’s main line-up has lasted much longer than any Dire Straits line-up. Also in 1996, Knopfler recorded guitar for Ted Christopher’s Dunblane massacre tribute cover, Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.

Knopfler composed his first film score in 1983 for Local Hero. In 1997, Knopfler recorded the soundtrack for the movie Wag the Dog. During that same year Rolling Stone magazine listed Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame’s 500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll, which included “Sultans of Swing”, Dire Straits’ first hit. 2000 saw the release of Knopfler’s next solo album, Sailing to Philadelphia. This has been his most successful to date, possibly helped by the number of notable contributors to the album, like Van Morrison. On 15 September 1997, Knopfler appeared at the Music for Montserrat concert at the Royal Albert Hall, London, performing alongside artists such as Sting, Phil Collins, Elton John, Eric Clapton and Paul McCartney.55

In July 2002, Knopfler gave four charity concerts under the name of “Mark Knopfler and friends” with former Dire Straits members John Illsley, Chris White, Danny Cummings and Guy Fletcher, playing old material from the Dire Straits years.56 The concerts also featured The Notting Hillbillies with Brendan Croker and Steve Phillips. At these four concerts (three of the four were at the Shepherd’s Bush, the fourth at Beaulieu on the south coast) they were joined by Jimmy Nail, who provided backing vocals for Knopfler’s 2002 composition Why Aye Man.

Also in 2002, Knopfler released his third solo album, The Ragpicker’s Dream. In March 2003 he was involved in a motorbike crash in Grosvenor Road, Belgravia and suffered a broken collarbone, broken shoulder blade and seven broken ribs.57 The planned Ragpicker’s Dream tour was subsequently cancelled, but Knopfler recovered and returned to the stage in 2004 for his fourth album, Shangri-La.

Knopfler performing in Hamburg, 2006 Shangri-La was recorded at the Shangri-La Studio in Malibu, California, in 2004, where the Band had made recordings years before for their documentary/movie, The Last Waltz. In the promo for Shangri-La on his official website, he said his current line-up of Glenn Worf (bass), Guy Fletcher (keyboards), Chad Cromwell (drums), Richard Bennett (guitar), and Matt Rollings (piano) “…play Dire Straits songs better than Dire Straits did.” The Shangri-La tour took Knopfler to countries such as India and the United Arab Emirates for the first time. In India, his concerts at Mumbai and Bangalore were well received, with over 20,000 fans at each concert.

In November 2005 a compilation, Private Investigations: The Best of Dire Straits & Mark Knopfler was released, consisting of material from most of Dire Straits’ studio albums and Knopfler’s solo and soundtrack material. The album was released in two editions, as a single CD (with a grey cover) and as a double CD (with the cover in blue), and was well received. The only previously unreleased track on the album is All the Roadrunning, a duet with country music singer Emmylou Harris, which was followed in 2006 by an album of duets of the same name.

Released in April 2006, All the Roadrunning reached No. 1 in Denmark and Switzerland, No. 2 in Norway and Sweden, No. 3 in Germany, The Netherlands and Italy, No. 8 in Austria and UK, No. 9 in Spain, No. 17 in the United States (Billboard Top 200 Chart), No. 25 in Ireland, and No. 41 in Australia. All the Roadrunning was nominated for “Best Folk Rock/Americana Album” at the 49th Grammy Awards (11 February 2007) but lost out to Bob Dylan’s nomination for Modern Times.

Joined by Emmylou Harris, Knopfler supported All the Roadrunning with a limited—15 concerts in Europe, 1 in Canada, and 8 in the United States—but highly successful tour of Europe and North America. Selections from the duo’s performance of 28 June at the Gibson Amphitheatre, Universal City, California, were released as a DVD entitled Real Live Roadrunning on 14 November 2006. In addition to several of the compositions that Harris and Knopfler recorded together in the studio, Real Live Roadrunning features solo hits from both members of the duo, as well as three tracks from Knopfler’s days with Dire Straits.

Knopfler at the NEC in Birmingham, England, 16 May 2008 A charity event in 2007 went wrong: a Fender Stratocaster guitar signed by Knopfler, Clapton, Brian May, and Jimmy Page, which was to be auctioned for £20,000 to raise the money for a children’s hospice, was lost when being shipped. It vanished after being posted from London to Leicestershire, England.” Parcelforce, the company responsible, agreed to pay £15,000 for its loss.5859

Knopfler released his fifth solo studio-album, Kill to Get Crimson, on 14 September 2007 in Germany, 17 September in the UK and 18 September in the United States. During the autumn of 2007 he played a series of intimate ‘showcases’ in various European cities to promote the album. A tour of Europe and North America followed in 2008.

Continuing a pattern of high productivity through his solo career, Knopfler began work on his next studio album, entitled Get Lucky, in September 2008 with long-time bandmate Guy Fletcher, who again compiled a pictorial diary of the making of the album on his website.60 The album was released on 14 September the following year and Knopfler subsequently undertook an extensive tour across Europe and America. The album met with moderate success on the charts (much of it in Europe) reaching No. 1 only in Norway but peaking in the Top 5 in most major European countries (Germany, Italy, The Netherlands). The album peaked at No. 2 on the Billboard European Album chart and at No. 5 on the Billboard Rock Album chart.61

Knopfler performing in Zwolle, Netherlands, 2013 Knopfler’s solo live performances can be characterised as relaxed—almost workmanlike. He uses very little stage production, other than some lighting effects to enhance the music’s dynamics. He has been known to sip tea on stage during live performances. Richard Bennett, who has been playing with him on tour since 1996, has also joined in drinking tea with him on stage. On 31 July 2005, at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre in Vancouver, BC, the tea was replaced with whisky as a “last show of tour” sort of joke.62

In February 2009, Knopfler gave an intimate solo concert at the Garrick Club in London. Knopfler had recently become a member of the exclusive gentlemen’s club for men of letters.63 In 2010, Knopfler appeared on the newest Thomas Dolby release, the EP Amerikana. Knopfler performed on the track 17 Hills.64 In February 2011, Knopfler began work on his next solo album, Privateering, once again working with Guy Fletcher. In July 2011, it was announced that Knopfler would take time out from recording his new album to take part in a European tour with Bob Dylan during October and November.65 The next year Knopfler covered a Bob Dylan song, “Restless Farewell”, for an Amnesty International 50th Anniversary celebration record.66

On 3 September 2012, Knopfler’s seventh solo album, Privateering, was released.67 This was Knopfler’s first double album solo release and contained 20 new songs. After a further tour with Bob Dylan in the US during October and November,68 the Privateering tour of Europe followed in Spring/Summer 2013.69 A short run of five shows were played in the US that Autumn.70 Knopfler began work on another studio album in September 2013, again at his British Grove Studios in London with Guy Fletcher co-producing.71 On 16 September 2014, it was announced that this new album would be entitled Tracker, and that it would see a release in early 2015. European tour dates were also announced for Spring/Summer 2015.72 In 2016 he collaborated with the Italian bluesman Zucchero Fornaciari playing in Ci si arrende and Streets of Surrender (S.O.S.) contained in Black Cat.

With the November release of 2018’s Down the Road Wherever, a Mark Knopfler world tour in support of the new album was announced for 2019. During interviews, Knopfler hinted it would be his last one. The tour started with a show on 25 April in Barcelona73 during which Knopfler confirmed to the live audience that the on-going tour would be his last tour ever. However, during the tour this statement softened,74 stating he will continue as he loves touring so much, joking he’d be unemployed and doesn’t know what else to do.

Knopfler appears in Cliff Richard’s song “PS Please” included on the Richard album Music… The Air That I Breathe released in 2020.

Knopfler penned the score for the musical version of Local Hero, including new songs alongside adding lyrics to the original instrumental music, reuniting again with Bill Forsyth.75

In January 2024, Knopfler announced his latest album, One Deep River, which was released in April 2024.76

Country musicedit

Knopfler performing in Chicago with Emmylou Harris, 2006 In addition to his work in Dire Straits and solo, Knopfler has made several contributions to country music. In 1988 he formed country-focused band the Notting Hillbillies,18 with Guy Fletcher, Brendan Croker and Steve Phillips. The Notting Hillbillies sole studio album, Missing…Presumed Having a Good Time was released in 1990 and featured the minor hit single “Your Own Sweet Way”. Knopfler further emphasised his country music influences with his collaboration with Chet Atkins, Neck and Neck, which was also released in 1990. “Poor Boy Blues”, taken from that collaboration, peaked at No. 92.

Knopfler’s other contributions include writing and playing guitar on John Anderson’s 1992 single “When It Comes to You” (from his album Seminole Wind). In 1993 Mary Chapin Carpenter also released a cover of the Dire Straits song The Bug. Randy Travis released another of Knopfler’s songs, “Are We in Trouble Now”, in 1996. In that same year, Knopfler’s solo single “Darling Pretty” reached a peak of No. 87.

Knopfler collaborated with George Jones on the 1994 The Bradley Barn Sessions album, performing guitar duties on the classic J.P. Richardson composition “White Lightnin’”. He is featured on Kris Kristofferson’s album The Austin Sessions, (on the track “Please Don’t Tell Me How The Story Ends”) released in 1999 by Atlantic Records.

In 2006, Knopfler and Emmylou Harris made a country album together titled All the Roadrunning, followed by a live CD-DVD titled Real Live Roadrunning. Knopfler also charted two singles on the Canadian country music singles chart. Again in 2006, Knopfler contributed the song “Whoop De Doo” to Jimmy Buffett’s Gulf and Western style album Take the Weather with You. In 2013, he wrote and played guitar on the song “Oldest Surfer on the Beach” to Buffett’s album Songs From St. Somewhere.

Musical styleedit

Knopfler is left-handed, but plays the guitar right-handed.77 In its review of Dire Straits’ Brothers in Arms in 1985, Spin commented, “Mark Knopfler may be the most lyrical of all rock guitarists.“78 In the same year, Rolling Stone commended his “evocative” guitar style.79 According to Classic Rock in 2018, “The bare-boned economy of Knopfler’s songs and his dizzying guitar fills were a breath of clean air amid the lumbering rock dinosaurs and one-dimensional punk thrashers of the late 70s. He was peerless as craftsman and virtuoso, able to plug into rock’s classic lineage and bend it to sometimes wild forms. He wrote terrific songs, too: taut mini-dramas of dark depths and dazzling melodic and lyrical flourishes.“3 Knopfler is also well known for playing fingerstyle exclusively, something he attributed to Chet Atkins.citation needed

Personal lifeedit

Knopfler has been married three times, first to Kathy White, his long-time girlfriend from school days. They separated before Knopfler moved to London to join Brewers Droop in 1973.18 Knopfler’s second marriage in November 1983 to Lourdes Salomone produced twin sons, who were born in 1987.44 Their marriage ended in 1993. On Valentine’s Day 1997 in Barbados, Knopfler married British actress and writer Kitty Aldridge, whom he had known for three years.80 Knopfler and Aldridge have two daughters.8182188384

Knopfler is a fan of Newcastle United F.C.85 “Going Home (Theme of the Local Hero)” is used by Newcastle United as an anthem at home games. Knopfler also has a collection of classic cars which he races and exhibits at shows, including a Maserati 300S and an Austin-Healey 100S.8687

Knopfler was estimated to have a fortune of £75 million in the Sunday Times Rich List of 2018, making him one of the 40 wealthiest people in the British music industry.88

In January 2024, more than 120 of Knopfler’s guitars and amps were sold at auction in London for a total of more than £8 million, 25 per cent of which will be donated to charities. Included in the auction was the 1983 Les Paul used for hits like “Money For Nothing” and “Brothers in Arms.” Knopfler expressed his desire for the instruments to find loving homes and hopes they will be played rather than stored away.89

Discographyedit

Main articles: Dire Straits discography and Mark Knopfler discography | Dire Straits albums - Dire Straits (1978) - Communiqué (1979) - Making Movies (1980) - Love over Gold (1982) - Brothers in Arms (1985) - On Every Street (1991) Solo albums - Golden Heart (1996) - Sailing to Philadelphia (2000) - The Ragpicker’s Dream (2002) - Shangri-La (2004) - Kill to Get Crimson (2007) - Get Lucky (2009) - Privateering (2012) - Tracker (2015) - Down the Road Wherever (2018) - One Deep River (2024) | Soundtrack albums - Local Hero (1983) - Cal (1984) - Comfort and Joy (1984) - The Princess Bride (1987) - Last Exit to Brooklyn (1989) - Wag the Dog (1998) - Metroland (1999) - A Shot at Glory (2002) - Altamira (2016) with Evelyn Glennie Collaborative albums - Missing…Presumed Having a Good Time (1990) as a member of The Notting Hillbillies - Neck and Neck (1990) with Chet Atkins - All the Roadrunning (2006) with Emmylou Harris - Real Live Roadrunning (2006) with Emmylou Harris | |—|—|

Honours and awardsedit

- 1983 BRIT Award for Best British Group (with Dire Straits)90

- 1986 Grammy Award for Best Rock Vocal Group (with Dire Straits) for “Money for Nothing"91

- 1986 Grammy Award for Best Country Instrumental Performance (with Chet Atkins) for “Cosmic Square Dance"91

- 1986 Juno Award for International Album of the Year (with Dire Straits) for Brothers in Arms92

- 1986 BRIT Award for Best British Group (with Dire Straits)93

- 1987 BRIT Award for Best British Album (with Dire Straits) for Brothers in Arms94

- 1991 Grammy Award for Best Country Vocal Collaboration (with Chet Atkins) for “Poor Boy Blues"95

- 1991 Grammy Award for Best Country Instrumental Performance (with Chet Atkins) for “So Soft, Your Goodbye"95

- 1993 Honorary Doctor of Music from Newcastle University96

- 1995 Honorary Doctor of Music from the University of Leeds97

- 1999 OBE98

- 2001 Masiakasaurus knopfleri, a species of dinosaur, was named in his honour99

- 2003 Edison Award for Outstanding Achievement in the Music Industry100

- 2007 Honorary Doctor of Music from the University of Sunderland7

- 2009 Music Producers Guild Award for Best Studio for Knopfler’s British Grove Studios101

- 2009 ARPS Sound Fellowship97

- 2009 PRS Music Heritage Award97

- 2011 Steiger Award102

- 2012 Ivor Novello Lifetime Achievement Award97

- The asteroid 28151 Markknopfler is named after him.103

- 2018 Dire Straits inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

- 2018 Living Legend Award Scottish Music Awards104

Referencesedit

- ^Knopfler, Mark (2005–2013). “Mark Knopfler: Discography of studio albums”. Markknopfler.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^“Mark Knopfler Biography”. The Biography Channel. Archived from the original on 4 February 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ ab“Album of the Week Club Review: Dire Straits – Brothers in Arms”. Louder. 21 May 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^“The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time:Mark Knopfler”. Rolling Stone. 18 September 2003. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^Alexander, Michael (20 October 2017). “Dire Straits reunion ’not on the horizon’, says band founder John Illsley ahead of Tayside gigs”. The Courier of Dundee. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^“Dire Straits given plaque honour”. BBC. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ ab“Sunderland honours Sultan of Swing”. University of Sunderland. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^“Third Honorary Degree”. MarkKnopfler.com. 5 July 2007. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^Greene, Andy (13 December 2017). “Nina Simone, Bon Jovi, Dire Straits Lead Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 2018 Class”. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^“Erwin Knopfler”. Billwall.phpwebhosting.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^“Chess Scotland”. Chess Scotland. 27 November 2005. Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^“AHF Presents: Nobel Prize Winners and Famous Hungarians: The American Hungarian Federation, founded 1906 (hires magyarok es olimpiai bajnokok) – Film, Arts and Media”. Americanhungarianfederation.org. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^“BIOGRAPHY: Mark Knopfler Lifetime”. Lifetimetv.co.uk. 12 August 1949. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^“Mark (Freuder) Knopfler”. Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^“Erwin Knopfler (1909–1993)”. Chess Scotland. Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^Irwin, Colin. Dire Straits. Orion, 1994. ISBN 1-85797-584-7.

- ^“Chess Scotland”. Chessscotland.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ^ abcdefghKilburn, Terry. “Mark Knopfler Authorized Biography”. Mark Knopfler News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^Robson, Ian (18 March 2015). “Mark Knopfler immortalises The Chronicle in song on new album”. Chroniclelive.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^“Mark Knopfler Live @ Madison Square Garden 2019 Revisited. Full concert”. Retrieved 19 November 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^“Harlow College – Home”. Harlow-college.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^“Chaos on the Sheepscar Interchange”. Leedstoday.net. Retrieved 27 September 2014.permanent dead link

- ^“Duolian String Pickers Days”. Markknopfler.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^“Who’s been here | About the University | University of Leeds”. 16 October 2006. Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^Steve Huey. “The Booze Brothers – Brewers Droop”. AllMusic. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^Kilburn, Terry. “Mark Knopfler Biography”. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^Genzel, Christian. “David Knopfler”. AllMusic. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ ab“Dire Straits Biography”. Sing365.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^Young, Andrew (17 July 1982). “On the right track”. The Glasgow Herald. p. 7. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^Hunter, Alan; Astaire, Mark (1983). Local Hero: The Making of the Film. Edinburgh: Polygon Books. p. 39. ISBN 978-0904919677.

- ^“BAFTA Awards”. BAFTA Awards. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^“Local Hero (Original Soundtrack) – Mark Knopfler”. AllMusic. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^David Nieri. “Mark Knopfler – The Long Highway”. pp. 38–43.

- ^Paul Sexton, They were different days

- ^“Summer of 1985: Eleven Top Music Moments Remembered”. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^“Archived copy”. Knopfler.net. Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2022.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^CLASSIC TRACKS: Dire Straits ‘Money For Nothing’. soundonsound.com

- ^Terry Williams Interview March 2013 (soundcloud) (around 1:01:39, 1:02:13-1:03:40)

- ^Strong, M.C. (1998) The Great Rock Discography, p. 207.

- ^“Mark Knopfler hurt in crash”. BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^“Queen head all-time sales chart”. BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^“Digitally Recorded, Digitally re/mixed and Digitally Mastered (psg)”. News.ecoustics.com. 16 August 2007. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^“David Gilmour – DVD Draw”. Davidgilmourblog.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ ab“Mark Knopfler Authorized Biography”. Mark-knopfler-news.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^Whitburn, Joel (2002). Joel Whitburn’s Rock Tracks: Mainstream Rock 1981-2002: Modern Rock, 1988-2002: Bonus Section! Classic Rock Tracks, 1964–1980. Record Research. p. 48.

- ^“Dire Straits Biography on Enotes.com”. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2014 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^Gregory, Andy (2002). The International Who’s Who in Popular Music 2002. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781857431612. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^Rees, Paul (June 2015). “The sultan of swing”. Classic Rock #210. p. 124.

- ^McCormick, Neil (5 September 2012). “Mark Knopfler: how did we avoid disaster?”. The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ abYoungs, Ian (7 October 2008). “Entertainment | Knopfler declines Straits reunion”. BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ^Pilley, Max (5 November 2023). “Dire Straits turn down “huge amounts of money” to reform”. NME. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^“Dire Straits are in demand as ‘huge amounts offered’ for reunion”. The Independent. 4 November 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^Irwin, Corey (5 November 2023). “Dire Straits Has Turned Down ‘Huge Amounts of Money’ to Reunite”. Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^“Dire Straits given plaque honour”. BBC News. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^Billboard 6 September 1997. 6 September 1997. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^“PICTURES: Who remembers when Dire Straits rocked the New Forest?”. Daily Echo. 10 January 2022. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^Davies, H. “Rock star hurt in motorcycle crash”, The Telegraph, 19 March 2003

- ^“Star-signed guitar lost in post”. BBC. 7 December 2007. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^PR Inside.com (Retrieved 6 March 2008), Legend’s guitar lost in post

- ^“2007gfrdhome”. Guyfletcher.co.uk. 30 March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^“The Official Community of Mark Knopfler”. Markknopfler.com. 27 May 2009. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ^“2005 Shangri-La Tour Diary”. Guy Fletcher Website. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^Deedes, Henry (18 February 2009). “Knopfler serenades Garrick chums”. The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 17 January 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^“Thomas Dolby Prepares to Release First New Studio Album in 20 Years”. Thomas Dolby Website. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^“Mark to tour with Bob Dylan”. Mark Knopfler Official Website. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^Terry Kilburn (20 January 2012). “Amnesty International’s Chimes of Freedom – Update”. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^“Mark’s New Solo Album – Privateering”. MarkKnopfler.com. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012.

- ^“Guy Fletcher, home of Dr Fletch, Mark Knopfler Keyboard Player and Solo Artist Inamorata”. Guyfletcher.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^“2013 Mark Knopfler European Tour Diary by Guy Fletcher”. Guyfletcher.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^“2013 MK USA Tour”. Guyfletcher.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^“Guy Fletcher, home of Dr Fletch, Mark Knopfler Keyboard Player and Solo Artist Inamorata”. Guyfletcher.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^Kilburn, Terry (16 September 2014). “New album and European tour dates”. MarkKnopfler.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^“Mark Knopfler Announces 2019 “Down the Road Wherever” World Tour”. Music News Net. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^Masley, Ed. “Mark Knopfler makes a solid case for not retiring when 2019 tour hits Phoenix”. azcentral. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^Brooks, Libby (11 March 2019). “Mac’s back: Scotland’s treasured Local Hero is reborn as a musical”. The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^Murray, Robin (24 January 2024). “Mark Knopfler Announces New Album One Deep River | News”. Clash. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^“10 Famous Left-Handed Guitarists Who Play Right-Handed”. Ultimate Guitar. 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^Brooks, E. (August 1985). “Dire Straits – Brothers in Arms”. Spin. p. 30.

- ^Schruers, Fred (19 December 1985). “The Year in Records 1985”. Rolling Stone. No. 463–464. p. 150.

- ^Wright, M. (1997) The Mirror, London, England. Available from: “Mark Ties the Knot-fler Again; TV Kitty Is Wife No 3 in Paradise Wedding"Archived 12 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- ^“Dire Straits legend loses planning battle”. Daily Echo. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^Palmer, Katie (23 June 2021). “Issy Knopfler dad: Who is the Before We Die star’s famous father?”. Express.co.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^Rix, Juliet (7 April 2007). “Cultureshock”. The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 May 2022. The novelist Kitty Aldridge and her daughter Issy study the form book at the dog track, then exhaust themselves on sweets and rides at Legoland

- ^Shillcock, Francesca (16 June 2021). “Before We Die: This cast member has a very famous dad – find out more”. HELLO!. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^Anthony Bateman (2008). “Sporting Sounds: Relationships Between Sport and Music”. p. 186. Routledge

- ^Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: A Performer’s Passion: Mark Knopfler, Racer (Documentary). London: Speedvision. 2006.

- ^“Le Mans Classic”. Healey Sport. 2006. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^Hanley, James (10 May 2018). “Paul McCartney tops 2018 Sunday Times list of richest musicians”. Musicweek.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^Steven McIntosh; Noor Nanji (1 February 2024). “Dire Straits star Mark Knopfler’s guitars sell for more than £8m at auction”. BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^“The BRITs 1983”. Brit Awards. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ ab“Grammy Awards 1986”. Awards & Shows. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^“Dire Straits”. JUNO Awards. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^“The BRITs 1986”. Brit Awards. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^“The BRITs 1987”. Brit Awards. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ ab“33rd Grammy Awards 1991”. Rock on the Net. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^“Knopfler opens students’ studios”. BBC. 4 December 2001. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ abcd“Mark Knopfler”. Linn Records. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^“Order of the British Empire”. BBC. 31 December 1999. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^Perlman, David (3 April 2003). “Scientists find cannibal dinosaur”. San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: “Mark Knopfler – What it is Edison Music Awards −03”. 28 May 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2009 – via YouTube.

- ^“British Grove wins Best Studio accolade”. Neve. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^“Preisträger”. Der Steiger Award. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^“28151 Markknopfler (1998 UG6)”. JPL Small-Body Database. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^“Stars out in force for Scottish music awards”. News and Star. 2 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

Further readingedit

- Illsley, John (2021). My Life in Dire Straits : The Inside Story of One of the Biggest Bands in Rock History. London, UK: Bantam Press. ISBN 978-1-78763-436-7. OCLC 1282301626.

External linksedit

- Mark Knopfler at AllMusic

- Mark Knopfler at IMDb

| - v - t - e Mark Knopfler |

|---|

| Studio albums |

| Soundtracks |

| Collaborations |

| Compilations |

| Extended plays |

| Singles |

| Other songs |

| Videography |

| Musicals |

| Band personnel |

| Tours |

| Related articles |

| - v - t - e Dire Straits |

|---|

| - Mark Knopfler - John Illsley - Pick Withers - David Knopfler - Alan Clark - Hal Lindes - Terry Williams - Guy Fletcher - Jack Sonni |

| Studio albums |

| Live albums |

| Compilations |

| EPs |

| Singles |

| Tours |

| Related articles |

-  Category Category |

| - v - t - e Rock and Roll Hall of Fame – Class of 2018 |

|---|

| Performers |

| Early influences |

| Singles |

Authority control databases |

|---|

| International |

| National |

| Artists |

| People |

| Other |

This site only collects related articles. Viewing the original, please copy and open the following link:Mark Knopfler - Wikipedia